Arabic calligraphy developed with the advent of Islam in the 7th century. The writing of the Qur’an played a central role: indeed, copies of the sacred text can only be made in handwriting that is always neat, unlike that used in administrative documents. Thus, the “beautiful writing” of the Arabic language appears above all in the Koranic manuscripts. Later on, it also adorned works of a secular nature, art objects, and monuments, thus becoming one of the characteristic features of Islamic art.

The oldest preserved manuscripts of the Qur’an date from the late seventh and eighth centuries. They are copied in a script called Hijazi, with letters often slender and slanted, characterized by a simple layout. From the ninth century onwards, Arabic writing aimed at aesthetic perfection with a new calligraphic style known as “kufic” (after the city of Kufa in Iraq) or “angular.” It is characterized by sharp edges between the horizontal part (base) and the letters’ vertical part (shaft). To respect the layout, the calligrapher modulates the characters, lengthening, stretching, or narrowing them. Some pages of manuscripts present only a few lines of kufic writing, which explains why some prestigious Korans are made up of several dozen volumes.

In the tenth century, paper supplanted parchment, allowing for increasingly massive production of books in the Arab world. Other calligraphic styles developed, such as the so-called “cursive” scripts, with a more flexible and rounded line. Very varied, they break with the graphic unity of Kufic. The Naskhi is then spread in the Muslim East, the maghrib in the Maghreb, and Muslim Spain.

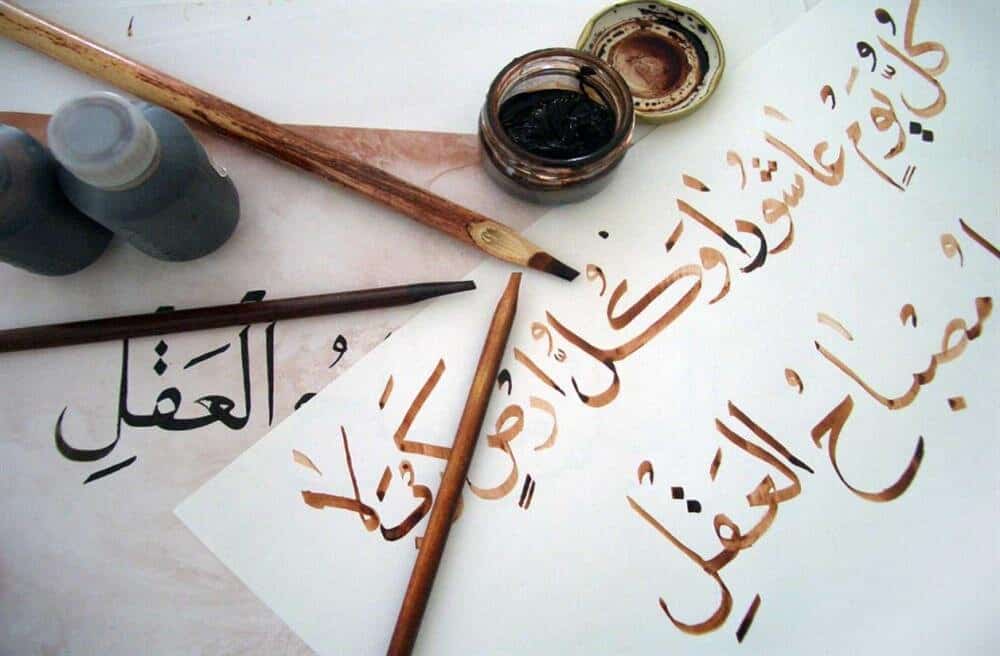

Arabic calligraphy became a major art form throughout the Islamic world, codified by prestigious masters such as Ibn Mouqla or Ibn al-Bawwab. These two calligraphers, who lived at the court of Baghdad in the tenth and eleventh centuries, established a system of rules theorizing a “well-proportioned writing,” making calligraphy a rigorous discipline. The calligrapher traces with the calamus – the beveled reed used as a writing instrument – a reference circle starting from the alif, the first letter of the alphabet. All the other letters of the alphabet must be inscribed in this circle. A measuring point then determines the proportions of each letter. The shape of the letters forces calligraphers to do a lot of research using these circles and reference points. The writing becomes perfectly legible.

In the 13th century, in Baghdad, Yaqut al-Mustasimi perfected the Naskhi and defined six canonical calligraphic styles: Naskhi, muhaqqaq, thuluth, riqa, rayhani, and tawqi. These styles were brilliantly cultivated throughout the Muslim East from the 14th century onwards. The Persians and Ottomans, who adopted the Arabic alphabet to write their language, i.e., Persian and Turkish language, gave a new impulse to these different styles. They also invented new ones, such as Nastaliq.

With its rules and styles, Arabic calligraphy was, therefore, the subject of rigorous teaching. Besides manuscripts, inscriptions also appear in specific compositions, often in a sacred context. They magnify architecture, ceramics, and the arts of metal, glass, and textiles. Calligraphic friezes appear on these different supports, embellished with geometric or vegetal ornaments. In addition to its practical function, calligraphy assumes a decorative role that sometimes emphasizes a strong symbolic dimension. Even today, contemporary calligraphers continue to develop this art. Writing styles such as Naskhi and maghribi are still in use.